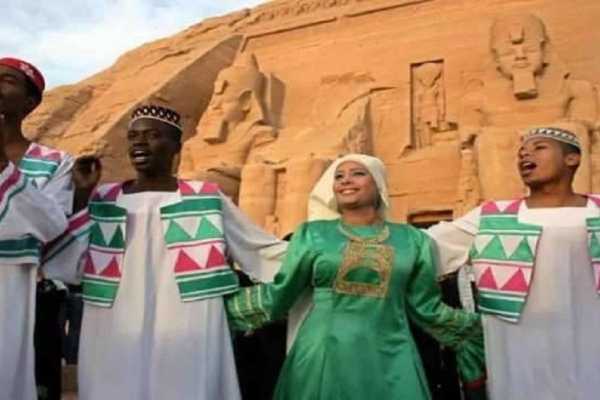

Queen Hatshepsuit 's temple

Who Was Hatshepsut?

Hatshepsut was born circa 1508 B.C. Beginning in 1478 B.C., Queen Hatshepsut reigned over Egypt for more than 20 years. She served as queen alongside her husband, Thutmose II, but after his death, she claimed the role of pharaoh while acting as regent to her step-son, Thutmose III. She reigned peaceably, building temples and monuments, resulting in the flourishing of Egypt. After her death, Thutmose III erased her inscriptions and tried to eradicate her memory.

Family

The only child born to the Egyptian king Thutmose I by his principal wife and queen, Ahmose, Hatshepsut was expected to be queen. After the death of her father at age 12, Hatsheput married her half-brother Thutmose II, whose mother was a lesser wife — a common practice meant to ensure the purity of the royal bloodline. During the reign of Thutmose II, Hatshepsut assumed the traditional role of queen and principal wife.

From Regent to Pharoah

Thutmose II died after a 15 year reign, making Hatshepsut a widow before the age of 30. Hatshepsut had no sons — only a daughter, Neferure — and the male heir was an infant, born to a concubine named Isis.

Since Thutmose III was too young to assume the throne unaided, Hatshepsut served as his regent. Initially, Hatshepsut bore this role traditionally until, for reasons that are unclear, she claimed the role of pharaoh. Technically, Hatshepsut did not ‘usurp’ the crown, as Thutmose III was never deposed and was considered co-ruler throughout her life, but it is clear that Hatshepsut was the principal ruler in power.

She began having herself depicted in the traditional king’s kilt and crown, along with a fake beard and male body. This was not an attempt to trick people into thinking she was male; rather, since there were no words or images to portray a woman with this status, it was a way of asserting her authority.

Hatshepsut’s successful transition from queen to pharaoh was, in part, due to her ability to recruit influential supporters, and many of the men she chose had been favored officials of her father, Thutmose I. One of her most important advisors was Senenmut. He had been among the queen’s servants and rose with her in power, and some speculate he was her lover as well.

Hatshepsut Temple and Achievements

Under Hatshepsut’s reign, Egypt prospered. Unlike other rulers in her dynasty, she was more interested in ensuring economic prosperity and building and restoring monuments throughout Egypt and Nubia than in conquering new lands.

She built the temple Djeser-djeseru ("holiest of holy places"), which was dedicated to Amon and served as her funerary cult, and erected a pair of red granite obelisks at the Temple of Amon at Karnak, one of which still stands today. Hatshepsut also had one notable trading expedition to the land of Punt in the ninth year of her reign. The ships returned with gold, ivory and myrrh trees, and the scene was immortalized on the walls of the temple.

Death

The queen died in early February 1458 B.C. In recent years, scientists have speculated the cause of her death to be related to an ointment or salve used to alleviate a chronic genetic skin condition - a treatment that contained a toxic ingredient. The testing of artefacts near her tomb has revealed traces of a carcinogenic substance. Helmut Wiedenfeld of the University of Bonn’s pharmaceutical institute has asserted, “If you imagine that the queen had a chronic skin disease and that she found short-term improvement from the salve, she may have exposed herself to a great risk over the years.”

Thutmose III

Late in his reign, Thutmose III began a campaign to eradicate Hatshepsut’s memory. He destroyed or defaced her monuments, erased many of her inscriptions and constructed a wall around her obelisks. While some believe this was the result of a long-held grudge, it was more likely a strictly political effort to emphasize his line of succession and ensure that no one challenged his son Amenhotep II for the throne.